Resources and Programming

While Resource Centers are not present at all colleges today– in fact, less than 15% of American colleges/universities had a full-time employee or dedicated graduate assistant dedicated to the needs of queer and trans students as of 2018 (Greathouse et al. 2018)– they have become a highly recommended best practice for schools looking to improve their campus climate for queer students. For example, a report by the CPEC (California Postsecondary Education Commission) recommended the creation of LGBT resource centers to reduce “the need for students to spend time on advocacy at the expense of their education.” They also said that “at a minimum, LGBT students should have access to a resource center or a designated advocate on campus” (Angeli 2009:3-4).

Research has found that LGBT resource centers provide an important point of entry for queer and trans students seeking support. They help create opportunities to connect and build a community, which helps with student’s sense of belonging on campus. Centers also help foster positive identity development and can impact campus climate. Furthermore, they serve an important purpose in taking the burden of creating and maintaining resources off of the backs of students, allowing them just to be students instead of having to provide resources, education, and support (Greathouse et al. 2018, Eveland 2023). These services are made all the more important as researchers have found that, in many cases, the college/university Center was often the only visible LGBTQ advocacy organization in the region, especially for rural schools. This gives them responsibilities within the larger community as well (Mundy 2018).

As for how exactly LGBT Resource Centers work to achieve these aims, their methods and goals vary widely based on the composition of the institution within which they are situated. Some centers see the core mission of LGBTQ centers as advocacy for LGBTQ students. This includes securing tangible resources and educating the broader campus (Mundy 2018). Others see them primarily as “safe spaces” where students can go to escape the marginalization and discrimination they experience in the rest of the world (Self and Hudson 2015). As demonstrated by Self and Hudson’s (2015:227) Spatial Analytic Matrix Model, these differing positionalities are largely determined by structural factors at the school-wide level (Self and Hudson 2015). Through my analysis of the LGBT Resource Center pages in my sample, I hope to explore further how the situating of these centers on campus is affected by the type of school they are located within and how this impacts the programming they offer.

Advertising Activism and Support Services

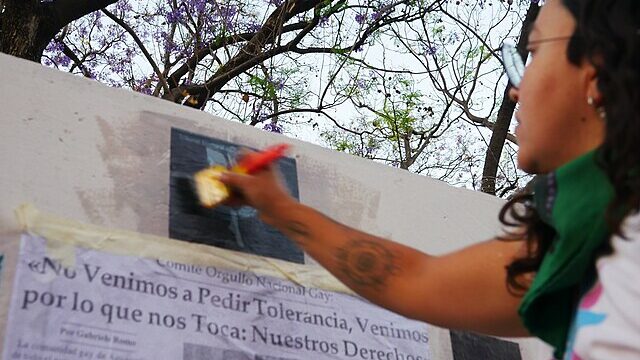

While I was unable to find any research that specifically addressed the ways that college LGBT Resource Centers advertised their programming to students, I was able to locate research that addressed the outreach strategies used by other forms of activist or support services that can be reasonably applied here. Research has found that other organizations and activist groups focused on the LGBTQ community prefer “ground-up” communication strategies (Mundy 2013). They believe that fundamental change will occur from the ground up, not the top down.

Towards this aim, their communications and outreach efforts focus on being positive and non-combative (Mundy 2013). However, it is important that these ground-up messages are relatable to members of the LGBT community if they want them to engage. As Ciszek (2017) points out, LGBT people, particularly youths, do not resonate with and engage with programs they do not see themselves represented in, including intersectional identities. This makes diverse representations of LGBT life and identity of critical importance in reaching out to LGBT youth and getting ground-up community building and activism off the ground. One way that service providers and activists specifically appeal to youth, including undergraduate college students, is through the use of social media. This is an outlet that young people trust and use for community building and information gathering (Buzzi and Allen 2020; Stvilia and Gibradze 2017; Megele and Buzzi 2020). Social media sites are also important tools for recruiting people to join groups and organizations as they help to amplify their voices and reach (Buzzi and Allen 2020).

Theoretical Framework

The analysis of the LGBT Centers in this study is positioned from a critical queer theoretical perspective. Historically, research on queer-spectrum and trans-spectrum people has been from the perspective of an outside cisgender-heterosexual (cishet) eye. This perspective individualizes hatred or fear of queer people and ignores the structures that normalize gender and sexuality and maintain homophobia as an excuse and reason for differential treatment. This places the focus of activism and resources on changing individuals’ feelings toward the place of queerness in people’s lives, rather than changing the invisible regulations that support the ideas of heterosexism and cisnormativity (Preston and Hoffman 2015). Framing research on marginalized populations must be critically examined to question this perspective (Duran, Jackson, and Lange, 2022).

Duran, Jackson, and Lange (2022:387) claim that by instead taking a queer theoretical approach, one ensures that “…LGBTQ+ people are not framed as subjects to be fixed. Instead, queer and trans frameworks understand that culture, environments, and institutions are antiqueer/trans spaces in need of transformation or deconstruction.” This positionality pivots the framework away from seeing centers as preventative measures focused on protecting an LGBT minority population towards being active forces of change-making with the ability to shake the foundations of the institution of higher education (Preston and Hoffman 2015). Queer theory should be applied to studies of LGBT centers to enhance understanding and address problems in the postsecondary system by questioning the normative binary constructions prevalent in our educational structures and the role that centers can/should have in changing them.