The Prioritization of Community Building

Across both types of schools, the most common program intention was Social/Entertainment, and Activism was among the least common. This figure shows the proportions of each programming intention for public schools, private schools, and all of the sampled schools:

This aligns with the stated desires of queer college students (Eveland 2023) as well as trends that show that Centers are moving away from their activism-centric roots and toward being safe spaces (Marine and Nicolazzo, 2014). Furthermore, those activism-based programs that did exist, only five in this sample of 60 programs, were directed off-campus. For example, this post is advertising one of the most explicitly activism-based programs in the sample, a “Queering the Vote” discussion held at NYU, which is aimed at general civic engagement, not campus government:

Therefore, Centers do not seem to see themselves as forces for active political change on campus.

Instead, it was implied that most centers saw themselves as pursuing change by fostering the building of a strong queer community. This was made evident by the wide range of social events oriented towards queer students which were offered across the schools. Many of these posts used explicitly community-based language. This included things like describing events as a place to “make new friends,” “connect with other students,” “form community through conversation,” and “build community and spread queer… joy.” For example, look at these two events, one a discussion on mental health in the queer community at Carleton College and one a mixer for LGBT graduate and professional students at the University of Michigan. Both use similar language and tone, despite their very different subject matters, and position community building as a solution in and of itself.

The overall tone of the programming advertisements reflected this intention, as they were very positive, with lots of exclamation points and bright colors.

Intersectionality

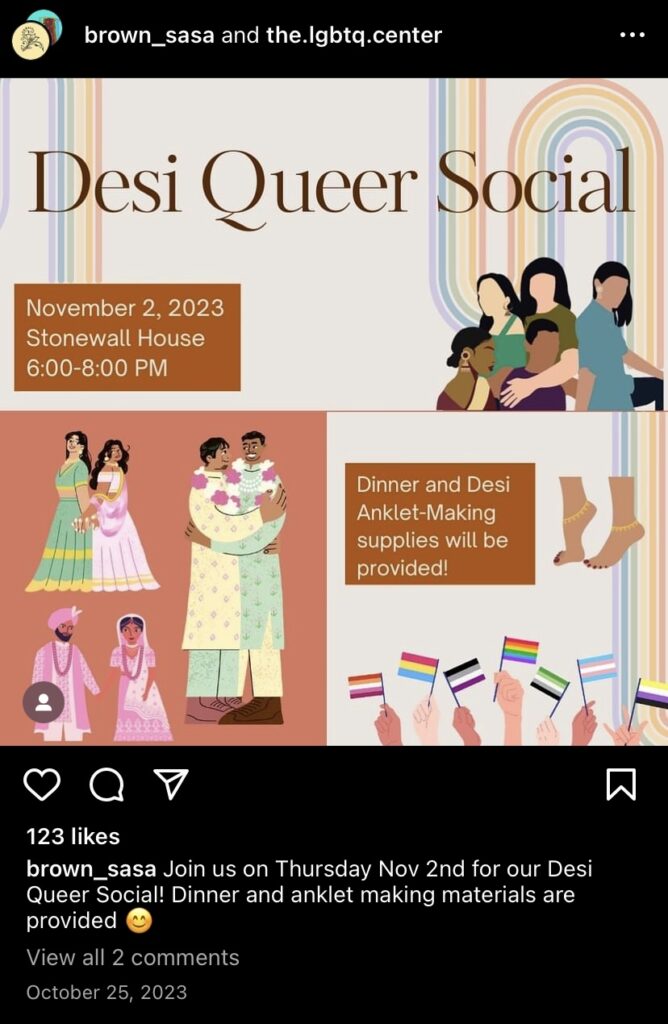

Related to activism is the Centers’ treatment of the intersectional nature of queer identity, which Centers in this sample did not seem to engage with intentionally. Intersectionality was rarely explicitly addressed in the posts. When it was, it was almost always in reference to exclusive spaces based on racial/ethnic identities, and these events were almost always cosponsored by an organization focused on racial/ethnic identity. For example, this post advertising a social for Queer Desi students at Brown was co-sponsored by the school’s South Asian Student Association:

Instead, the Centers tended to refrain from describing or depicting the intended audience for their events at all. They referred to events vaguely by using “LGBT” acronyms, “Queer,” or other Pride-related terminology and very few posts included pictorial representations of their intended audience. Sometimes this was so vague that the only cue that an event may be intended for queer people was the fact that it was posted by the LGBT Center. For example, this post advertising a “Paint & Board Games Night” at Stanford for which the only indication that the “community” they refer to building is the queer community is the inclusion of their center’s acronym which may not even be obviously queer if you do not know what it stands for:

These examples demonstrate a trend in which schools market their programming to one specific audience or market it so widely that the true audience is unknown. It could also indicate schools’ caution surrounding marketing events specifically for queer students out of fear of harassment or outing.